|

|

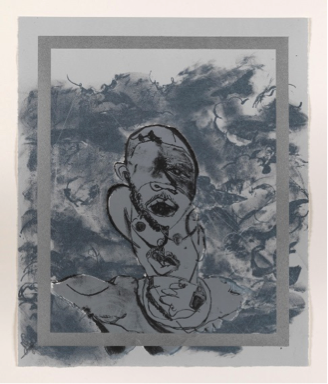

Interview with Jonathan Lyndon Chase on Forehead Kiss, October 11, 2018 (continued) Jonathan Lyndon Chase (American, b. 1989) Forehead Kiss, 2018 (detail) Stone and plate lithograph on Somerset Satin white paper, digital print on brown Two parts, 13 1/2 x 11 inches and 6 1/2 x 5 1/4 inches. Edition of 10. Published by the Brodsky Center at PAFA, Philadelphia

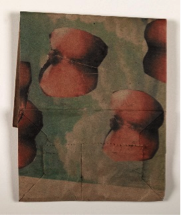

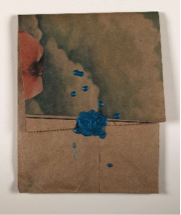

[clouds can't be stopped] In my work, I reference water and the different ways that it is symbolic of my culture and the body-from my religious background, to the African-American history of slave trade, and to how we express emotions. In this print, I began with the clouds. In my paintings, objects are endless compound and concurrent spaces. Clouds are always happening and moving, changing form and shape. In relation to gender, queerness, and blackness, clouds are a really interesting way to talk about change and flux, in reference to the body and identity. You can be in one kind of feeling or space one day, and another the next-maybe I want to become more butch or more feminine, or I want to change my outer appearance and gender performance. Clouds carry these ideas of performativity and fluidness. I also think a lot about the emotional and mental spaces inside the body. I talk about emotions being these really complex events inside our bodies that a lot of time we cannot see on the surface. Clouds being what I consider like the natural element or the weather, are recurring themes in my work. Clouds are nature, just like emotions are natural, specifically in relation to male bodies, or boys or men. Our culture does not allow for men to express feelings or mental health states because of the stigma around them. You can't stop rain, you can't stop the clouds. So, if you are feeling emotions, what does that mean, and what does that mean for the body or the space around you? I am not trying to give an answer, but I am referencing a certain way of talking about emotions: you really have to let an emotion go and be, like when it rains, you take an umbrella and prepare to navigate that space for that time. [mask and face pulsate] I think about time a lot-mortality, and also just about motion and natural illness, in different ways. In my work, bodies are beginning and ending into each other, wading through each other. They are parts of memory that are frozen within each other. The body absorbs, as on a surface or as embedded back into the landscape of the body. I try to visualize the body in this way: the unseen, psychological space of emotional space, the space between the bodies, which is the intimate space, and this really, really public space that's like boundless-the sky, the air, all around us. I think about freedom of liberation. There are three different spaces in Forehead Kiss-what you see on the surface, what you see internally, and the frame as its own space. In my paintings, framing devices act like a horizon for the figures; for example, beds often play this role. In the print, the "silver order" or frame is a visualized gaze from the perspective of the viewer, a window for looking deeper at something, but also to project onto bodies expectations that are sometimes, like on a surface, not at first glance visible, and yet that have really, really powerful, embedded long-lasting effects on both space and body. Time freezes and captures this dynamic at different points, through high-end emotions, like joy and love and despair and sadness-it's very fluid and complex. One of the dangers of toxic masculinity is to always feel one emotion constantly, which is not healthy or normal. Always being happy, or maniac, or feeling sad for an extended period of time is not healthy. For male bodies or masculinity, since the beginning of history, it's been about stoicism, lack of emotions, denying young boys and older men what is very human. Pulsing and moving, instead, are really important because, we are living, breathing things. The square in many cultures signifies harder, masculine grounding, but here the ground is not directly visible, it's an atmospheric, emotional space. I reference Francis Bacon, yet with a significant shift to an open space, to loving and tenderness and the loud, congested, hard way to just to be yourself. It is not a performative space where bodies are being adhered to expectations on the ground. Often times, I try to eliminate the distance between performance and private space. My public spaces are more theatrical, outside of a safe, domestic space; I see communal spaces, goings-on, or out-into-the-world, as stages for surveillance or watch or gazes projected upon you, in different kind of ways. In private space, there is de-masking and no performative quality. A lot of heads in my work are between mask and face. At times, they are about what one allows a person to see, at others they are about something deeper, more intimate. In the print, they are not masks, they are heads, bodies. They are not in a space where they have to perform; they are rather natural, tender, relaxed. [queer black bodies are loving] I am interested in the bodies in Bacon's paintings, which are full of despair and tension. But it is important to insert in popular culture and our history a positive, tender, intimate loving image of queer bodies and black bodies. Ultimately, our bodies are celebrated or fetishized through weird projections, and our pain is consumed so much, often more celebrated than our joy, in a comedic and mocking way. I really think it is important to have lots of images of our love and tenderness as a part of the canon of images. Bodies are also often shamed, de-normalized, through a constricted, non-flowing idea of what it means to be physically and visually a man. In this print and in my body of work, I am interested in painting what I would consider real. Bodies are beautiful, but beauty includes grotesqueness or nastiness at the same time. Like being very intimate or romantic, but then dealing with body fluids; or like many forms that two or multiple bodies assume for sex and intimacy, which includes a performative fantasy; or like male bodies that are often not seen, such as fat bodies, which are heavily shamed or fetishized. The body positivity movement that is happening in 2018 applies to men as well, even if they are often left out of that conversation because men have difficulties accepting those kinds of issues with themselves. This comes back to emotions, being open to talk about one's body. In my work, soft parts of the body are lined up with the hard parts. That's why line weight and sensitivity in my figures is important. I try to charge each line with an emotional quality and think about how a harder and a softer line can coexist. In the print, there is a push and a pull effect, letting the line recede and then come to the front, which derives from the alchemic process of printmaking, which allows the unknown to happen. In printmaking, each multiple is very similar but then also unique, with subtle differences that happen, which may not be visible to the eye, at first. Spending time with the printed image, looking deep into it allows you to see nuances. In the same way, we are all bodies, all human. These things really correspond to how in my paintings I draw double images and I use collage. The monochromatic aspect of the print reflects intimacy. My paintings have a lot of noise, taste, smells that are loud. The print is more harmonized or cohesive with nature and the cult of the natural in our bodies, which for the longest time were deemed unnatural. Monochrome was the most interesting way to talk about those things. [printmaking enables vulnerability] Working with master printer Peter Haarz has been fantastic. He shared processes and their historical origins, and compared his personal taste and practice versus how other master printers did it. I surrendered control and switched instead to trust and vulnerability, which I think coincides with many things that I talk about in my work; I had to share really intimate details conceptually, which was nice. I do not do that so often and I felt in this process it was really required, necessary to work with Peter to make the print. It was heavily time based, in a different way in which I am used to think about time, and it was wonderful just to take that to the studio-ultimately, the experience of a residency left an impression on my body, to come back to my painting and go through different ways of marking time; and I have fallen deeper in love with paper. It has been magical having that distance between the print and subsequent proofs, looking at an image that you came to multiplied many times. In Photoshop images are not printed out like multiples are. Seeing my work in different subtle or stark variations until the end product was really fantastic-and scary, as well, but in a great way! Doing a residency and working on a print definitely gave me courage to think about other aspects of my work, especially sound, in a more confident, experimental way that I would have not come into if I were not working on this print. The collage that I ended up printing on the ready-made brown bag accompanying the lithograph was the one work that I brought to the residency. The collage informed the printed image. A lunch paper bag is a simple stand-in for how air exits and enters the body, panic attacks, and just air, free but contained, a kind of pumping. And then it is monochromatic. The brown paper bag can also stand for a disparaging attitude, if we think of the history in America of the brown paper bag test-restricted, grounding, really violent; opposite of tender, freedom and being able to navigate change. The sound component in the edition is mine and my husband William's voices, with ambient noise, rain effects-different states of clouds. It also includes sounds the master printer made that I taped while he was printing, such as rolling or slamming. It's fluid, open, liberating, gender-flexing sound. Having the time to mediate and look, having a distance between states, gave me space to work on the sound components. I would come in the print shop and think about what sound might I hear that would be just right in a certain track, to pair or layer, just like the bodies are layered and are pushing back and forth with the clouds. I have done a few videos, but this is the first time that I let sound stand on itself, without a moving image, and I have never related it to a painting or drawing. I also like documenting, and for this print too I compiled archive binders with different documents and references, things that come together to make a single piece or a body of work. I was excited to think about printmaking and the residency itself as this really embedded and memorable process that has been solidified in different ways through the print and photography. It is a way to talk about my process, being equal parts intuitive and then having rules, parameters, a structure. I keep sound components and poetry all together because they are this one body of work, this one experience that is great to go back to and reflect upon. |